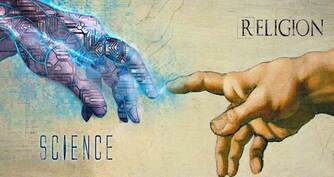

Religion and science are often seen to be in opposition to and suspicious of one another. Scientists like Richard Dawkins would see science as having superseded religion and religion and belief in God as superstitious and belonging to another age, believing that in science humankind has come of age. Some like the late Lord Jonathan Sacks would suggest that the two disciplines are asking different questions, one about how the universe works and the other about what meaning is to be found in the world as we know and experience it. But is this a satisfactory answer for surely what we now know about quantum mechanics, evolution and the origins of the universe can give meaning to our lives and influence our relationship to the environment and to our fellow human beings as much as religion can? If science and religion are windows into reality and are seeking truth in their own way, they can surely learn from one another, rather than fear one another. Pope Francis has said as much when he addressed scientists at a meeting of the Pontifical Academy of Science “we ought never to fear truth, not become trapped in our own preconceived ideas but welcome new scientific discoveries with an attitude of humility”.

Someone who is doing this and whom I have recently come across is Professor Steven Phelp, a physicist, philosopher, and member of the Baha’i faith whom I recently heard talk on religion and science. What he said made a lot of sense to me and is, I think, worth sharing. Science, he pointed out is seeking a truth greater than itself. After all it discovers truth, does not construct it, and is limited in its expression of this truth by historical circumstances or the state of knowledge at the time in which it was discovered. Stemming from an intuition about experience and observation of the world it sets up a hypothesis and, through the language of mathematics, comes to a conclusion which only later, and sometimes many years later, is confirmed by observation and experiment. So, Isaac Newton made a great breakthrough when he discovered gravity in the 17th cy. and while it truly expressed reality and has been useful for understanding relationships within the universe it is also wrong because it is based on a static notion of time and space which were at the time thought to be separate realities. It has been superseded by Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity which shows that space and time, like matter and energy can translate into one another and are therefore relative rather than absolute. And, suggests Prof. Phelps, Einstein’s theory will also be superseded as knowledge of quantum mechanics grows. Recognising the limitations of these theories does not invalidate them nor render them useless but it does contextualise them. It recognises that while reflecting aspects of the truth they do not contain the whole truth which is still waiting further discovery.

While I do not understand the science, I can see the similarities with religion. It too has an intuition about reality which it expresses in the language of analogy and myth, but it is also limited in its expression by the understandings of the cosmos prevalent at a given historical period. In a three-tiered universe the sense of Ultimate Reality was seen as existing in a higher dimension – heaven, paradise, nirvana - and the wonders of nature as a gift of a Creator or God – at least in most religions apart from Buddhism that does not posit a creator. Within the context of religions there are many ways of describing God or Ultimate Reality and different ways of relating, not just to that Reality. But all of them are conditioned, as the Buddhists would say, and need to be rethought in the light of scientific discoveries. As with science past theologies and religious categories can be true and useful for living a wholesome life but can appear limited and inadequate in another age. Therefore, they need to be rethought.

For Prof. Phelps science and religion are maps to help us understand and find meaning in a world which is essentially relational. But maps are always approximations of reality. They are not accurate descriptions of how things are but are useful for helping us negotiate and relate to reality. For a long time, I have felt that the way religious believers, religious liturgies speak of God and address God in prayer does not fit in with what we know of the universe. How can there be a God outside of time, seemingly existing in another dimension and waiting to direct us or answer our prayers or even punish us if we stray and reward us if we live a good life? This concept of God fits in to a three-tiered universe much better than our present understanding of the cosmos and it has been helpful to people in the past, perhaps to some even now but does not resonate with others. For these people, including myself, concepts such as Ultimate Reality, the Ground of Being, that Reality in which we live move and have our very being reflect what I know of the world and lead me to a sense of the Mystery that is at the heart of life. They do not trip off the tongue, however, and while God is a possible substitute for these there is a danger that a simple use of the word God obscures rather than reveals that Mystery and that many who reject any notion of God are doing so without understanding the nature of religious language or the Reality that it is pointing to.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed