Central to this interest in religion was a belief in God and I loved God with all my heart. It’s not that I had no theological questions but to accept a loving God came easily in spite of theologising about suffering and death. This sense of a relationship with a loving God was developed and deepened by daily meditation, reflection on the gospels and the teaching of Jesus, spiritual reading and the annual retreat that as a religious I am obliged to make. Eventually this notion of loving God expanded to believe that God loved me at the very core of my being and accepted me totally for who I am, strengthening me and supporting me as I struggled with life as we all do.

It took some time before I began to feel dissatisfied with the word God. The way people talked about God or addressed God in prayer made God into a superman or a Santa Claus- like figure. This was an interventionist God, who had created a world out of nothing and was able to oversee, control the world of humans. This was a God who made demands on people seeking that they do his will and able to intervene in all kinds of suffering from ending war, poverty and hunger to providing answers to more specific requests for healing or even good weather for the parish outing. This was a God that more and more people claimed not to believe in and a God that did not reflect my own experience. So my image of God began to change. Not only could I not accept that God was male but that God also had to reflect the feminine as both men and women were made in the image and likeness of God. And I could not believe in a God that was an all powerful being somewhere outside the bounds of the universe. Rather I believed that God was that Reality in which we all live, move and have our very being as the apostle Paul explained to the Greek philosophers on the Areopagus or the Ground of Being as Paul Tillich suggested. This was a God intimately involved in life and the best image I could come up with was that God was a kind of magnet, powerfully drawing us towards love and the fullness of life. This was a God whose power of attraction I had experienced throughout my life.

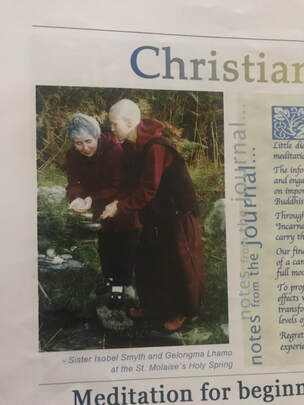

My interfaith journey has helped me see that this power of attraction is present in all faiths – and none. Buddhism is well known for not believing in a creator god and some people would go so far as to say that it is not a religion but rather a philosophy of life. One of the deepest and most significant dialogues that I have experienced was a Buddhist – Christian dialogue led by a Tibetan Buddhist nun, Ani Lhamo and myself. It began with a week on Iona and lasted about 15 years when we would meet annually in Samye Ling, Holy Isle, a Carmelite monastery as well as more ‘secular’ places. The week on Iona that began the dialogue remains in my memory as one of the most meaningful that I have experienced. Ani Lhamo and I spent the week talking, sharing our faith and preparing the sessions we were offering in the Abbey while enjoying the sun and beauty of the island. We became good friends, with a real sisterly connection and I for one recognised the common attraction we had to spirituality, an attraction that had led both of us to a lifetime of commitment in a religious community. I could relate this attraction to God but it did not seem to be so different from that of Ani Lhamo’s who did not believe in a creator God but did believe in a Reality that we participate in and draws us to itself. In Mahayana Buddhism this is called Tathata which is often translated as “suchness” and is seen as the true and essential nature of reality that is beyond description and conceptualisation and cannot be adequately expressed. This is the God of the christian mystics such as Meister Ekhart who famously said ‘ I pray to God to rid me of God’ realising that the word God can not only be off putting but obscure the truth of reality.

Hinduism has also taught me a lot about the Reality we call God. The vedic phrase ‘the Real is one though known by different names’ makes sense. The stories of young women being attracted by the Lord Krishna’s flute to dance the night away, believing that each of them had a unique and special relaionship with Krishna has resonance in my own experience and the notion of God with attributes and God without attributes allows for the tension between a personal God and an Impersonal Reality which is perhaps all I can hope for at this stage of my life.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed