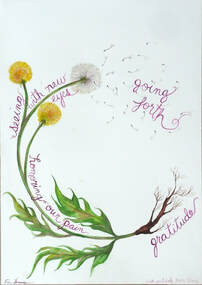

The process and sequence of the experiential side of the work is a spiral in which one begins with gratitude, moves through honouring our pain for the world and seeing with new eyes to going forth to contribute to the transformation of our planet in whatever way is ours to do. For Joanna Macy there are three possible approaches to life and we can choose which one to align ourselves with: business as usual, the great unravelling or the great turning which will bring about a peaceful, just and life sustaining society. It’s easy to see how each of these is manifest in the world today, especially the great unravelling.

The Great Turning spiral seems to me to reflect a profoundly human process and one that I would like to use in interreligious dialogue. What better place to begin than with gratitude. There’s much to be grateful for: the fact that interfaith relations has grown so much in recent years, that there can be strong friendships across religious differences, that we are able to respect one another even when our faiths are involved in conflicts in some parts of the world. We are all grateful for our own faith but perhaps some expression of our gratitude for the faith of others could be our starting point. What do we appreciate about one another’s faith, how are we helped by it, what wisdom do we find in the faith of others, how has knowing others helped illuminate our own faith? Gratitude is a great grounding for respect and friendship and for moving on to honouring our pain for the world.

Perhaps this is the movement in the spiral that we shy away from. It’s an interesting phrase – honouring our pain for the world. No-one can doubt the association of religions with violence and it’s easy for people of faith to dismiss this as a distortion of religion or bad religion and not what is at the heart of the faith. There will be some truth in this of course but we need to acknowledge, I think, the pain we have caused one another in the past by our preaching, forced conversions, teachings that suggest other faiths are somehow inferior to our own. We carry within our inherited memory suspicions and fears of the other and these memories can intrude in an unconscious way into the honesty of the dialogue. Pain and suffering does not belong simply to the past as we know from the islamophobia and anti-Semitism which has come to the fore in recent times. There are tensions between religions over citizenship as in Sri Lanka or Myanmar, over places of worship as in Ayodhya in India, over territory as in Israel and Palestine and while some of this is political it has religious implications for dialogue. To move forward and use our dialogue for peaceful co-existence can mean dialogue about difficult and controversial questions as well as the healing of memories. It does not mean repressing it for that can give it power over us. It means listening to one another’s stories, acknowledging them, recognising the imperfection and shortcomings of our faiths and searching for a common language with which to move forward. We honour the pain by transforming it for the sake of future relationships. This is a long slow process and I suspect that purposeful and profitable dialogues are more likely to take place in smaller groups and with a facilitator than in general public meetings, interesting as these might be.

Honouring our pain is important if we are to see with new eyes – ourselves as well as others, if we are to be able to stand in one another’s shoes, to understand and sympathise with one another while approaching them with humility. It is to delight in diversity while recognising a unity that transcends difference. What would it mean for a religion to show love for all the others and to work for their well-being? Would this not give hope to our world and be a great contribution to the Great Turning?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed